A Firefighter’s Guide to Fire Scene Size Up

A solid fire scene size up isn't just a box to check; it's the systematic evaluation that sets the tone for the entire operation. It's the foundation for every decision you make from the moment you roll up. This is where you rapidly process what you see to build a smart, safe, and effective initial action plan.

A quick but thorough assessment determines your initial strategy, tells you what resources you'll need, and, most importantly, keeps your crew safe.

Mastering the First Five Minutes on Scene

The first five minutes on any fire scene are everything. This is where the initial incident commander—usually from the officer's seat of the first-arriving engine—makes the calls that will define the incident's path. A methodical yet rapid fire scene size up isn't just another task; it's a dynamic mental process that kicks in the second you spot that smoke column from blocks away.

This initial look is your anchor. It’s all about reading the smoke, understanding the building's layout and construction, and trying to get one step ahead of the fire before your boots even hit the ground. Your ability to correctly interpret these signs informs the most critical decision of all: are we going inside for an offensive attack, or are we setting up for a defensive fight?

Interpreting Critical Cues from the Cab

Long before you pull the first line, the fire is talking to you. The smoke is the first thing it says, and you have to be fluent in its language. Zero in on its color, velocity, and pressure.

- Smoke Color: Is it light and white? That could signal an early-stage fire chewing on ordinary combustibles. Or is it thick, black, and boiling? That's a huge red flag for a ventilation-limited fire that's primed for a flashover.

- Velocity and Pressure: Is smoke just lazily drifting out of a window, or is it being pushed out with force like a freight train? High-velocity smoke is a dead giveaway for intense heat and a fire that's rapidly growing and pressurizing the whole structure.

Practical Example: You pull up to a two-story house and see light gray smoke puffing from the eaves. Your brain should immediately jump to a potential attic fire. But if you see dark, churning smoke blasting out of a single first-floor window, you're likely dealing with a well-advanced room-and-contents fire that's about to spread and will require a more aggressive initial attack.

This isn't just a glance; it's a comprehensive assessment to gauge the fire's severity and the dangers it presents. You're trying to nail down the fire's origin, how fast it's spreading, and where it's going next. This information is absolutely vital for picking the right tactics. A proper size up also means looking at the building's structural integrity and scanning for other hazards, like hazmat, to keep everyone on the scene safe. For a deeper dive, Emergent.tech has some great insights on comprehensive assessments.

The goal is to move from just reacting to what's in front of you to anticipating what the fire is going to do next. That predictive mindset, built on a rock-solid initial size-up, is what separates a chaotic, dangerous scene from a controlled, effective one.

This quick table can help you organize your thoughts as you arrive.

Initial Size Up Critical Observation Checklist

| Observation Cue | What It Tells You | Immediate Tactical Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Thick, Black, Turbulent Smoke | Ventilation-limited, high heat, potential for flashover. | Control the door, coordinate ventilation with attack, consider a transitional attack. |

| Light, White, Laminar Smoke | Early-stage fire, likely Class A materials. | Aggressive interior attack may be viable, check for extension. |

| Pulsing or Puffing Smoke | Fire is "breathing," indicating it's starved for oxygen. | Imminent backdraft potential. Do not open the structure without coordinated vertical ventilation. |

| Fire Showing from Windows | Active, well-ventilated fire in that specific area. | Direct attack on the seat of the fire, check for vertical/horizontal spread. |

| Sagging Roofline or Bowing Walls | Compromised structural integrity, potential for collapse. | Establish collapse zones, switch to a defensive strategy, get all personnel out. |

| No Visible Smoke or Fire | Could be a small, contained fire or a dangerous void space fire. | Proceed with caution, use a thermal imaging camera (TIC), investigate thoroughly. |

Keep this checklist in mind as a mental model to ensure you're not missing any critical pieces of the puzzle.

From Visuals to an Action Plan

What you see has to translate into an immediate action plan. The difference between a simple room-and-contents fire and a blaze that takes the whole building is often decided by your crew's first moves.

Practical Example: You arrive at a single-family home with heavy fire blowing out a front window. Your size up confirms a working fire. But then you notice the smoke coming from the attic vents is the same dark color and has the same velocity. That's a tell-tale sign of vertical extension. Your game plan now has to include not just knocking down the fire in the room of origin but also getting a line into the attic to cut it off.

This initial assessment is also about establishing clear command and setting the operational tempo for the whole incident. A quick, confident size-up report over the radio tells incoming units what you have, what your strategy is (offensive or defensive), and what their first assignments are. That clarity is what prevents freelancing and ensures everyone works together for a coordinated, safer operation from the very start.

Why the 360 Walk-Around Is Non-Negotiable

The view from the street is never the full story. Ever.

Relying solely on what you see when you pull up is one of the most dangerous gambles you can make on a fireground. This is precisely why the 360-degree walk-around isn't just a good idea—it's a fundamental, non-negotiable tactic that reveals the hidden truths of an incident.

Without a complete survey of the building, you're making life-or-death decisions with only a fraction of the information you need. That's a recipe for catastrophic mistakes.

Uncovering Hidden Hazards and Opportunities

Let's be blunt: the back and sides of a building often hide the most significant problems. Your walk-around is a deliberate hunt for these surprises before they find your crew. What you discover can completely upend your initial action plan.

Think about what you commonly find:

- Unseen Fire Conditions: That subtle wisp of smoke pushing from a sill plate on the "Charlie" side? That could be your only clue to a raging basement fire just waiting for someone to open the front door.

- Unexpected Hazards: Propane tanks for a grill, downed power lines sizzling in a wet backyard, or even an uncovered swimming pool can create immediate, serious dangers for firefighters.

- Access and Egress Issues: Barred windows on the rear of a building instantly eliminate a secondary means of egress. On the flip side, you might find a wide-open rear door or a walk-out basement that offers a much better entry point for an attack line.

This systematic survey is all about building a complete operational picture. A truly effective size-up hinges on the first-arriving officer completing a 360 to develop a comprehensive plan. It's the only way to visualize the fire's dynamics, spot hidden hazards, and make a sound risk-benefit analysis that guides your tactics.

The 360 Perspective on Different Structures

The value of a walk-around is universal, but the intel you gather changes drastically with the building type. What you're looking for at a single-family home is worlds apart from what you'll find at a commercial building.

Practical Example (Single-Family Home):

From the front, you see light smoke lazily drifting from the front door of a two-story colonial. But your 360 reveals heavy, black smoke churning from a second-floor window in the back and a homeowner screaming for help on a rear deck. Just like that, your priorities shift from a simple investigation to a known rescue and a confirmed working fire.

Practical Example (Commercial Taxpayer):

You roll up to a strip mall with smoke showing from a single storefront. Your 360 walk-around reveals that the rear of the building has multiple, unmarked utility connections and a shared cockloft running the entire length of the structure. This discovery tells you the fire has a clear path to every other business, instantly transforming your strategy from a single-unit fire to a potential multi-unit defensive operation.

The information you gather during your 360 has to get back to Command immediately. Clear, concise radio reports are key. "Command from Engine 1, 360 is complete. We have heavy fire from the rear, a walk-out basement on the Charlie side, and a compromised rear deck." That paints a complete picture for everyone on scene.

Conducting a Safe and Efficient 360

A walk-around needs to be done with purpose and an eye for safety. This isn't a casual stroll around the property. You're on an active fireground, and your head has to be on a swivel.

Here are a few practical tips for your next 360:

- Always Carry Your Tools: At a minimum, bring your radio, a good hand light, and a thermal imaging camera (TIC). The TIC is invaluable for spotting hidden fire behind walls or helping you locate victims.

- Stay Aware of Your Surroundings: Look up, down, and all around. Watch for wires, unstable ground, and tell-tale signs of structural collapse like bowing walls or sagging roofs.

- Communicate Your Path: Let your crew or Command know you're starting your 360 and which direction you're heading. "Engine 1 officer starting a 360, clockwise."

This simple act directly translates to firefighter safety and operational success. Knowing all sides of the story prevents us from sending crews into untenable conditions or missing a viable rescue.

Actionable Insight: Keeping this flow of information straight can be a challenge. Using incident management mobile apps ensures that crucial 360 findings are relayed instantly to every crew member, not just the IC. This prevents dangerous information gaps and reduces radio traffic, directly cutting down on operational errors that can lead to costly property damage or, worse, injuries.

Reading the Building to Predict Fire Behavior

A fire doesn't care about blueprints. It only cares about three things: fuel, heat, and oxygen. Every single structure you pull up to is telling you a story about how it will burn, and learning to read that story is a fundamental part of a solid fire scene size up.

When you understand a building's construction, it’s like having a cheat sheet for predicting fire behavior. You can anticipate collapse potential and make smarter, safer tactical decisions before you ever step off the truck.

This isn't some academic exercise. It directly impacts your strategy on the ground. Knowing a building's bones helps you predict how a fire will spread, moving you from a reactive to a proactive mindset. That predictive ability is what allows you to make better choices about where—and when—to commit your crews.

The Five Types of Building Construction

Buildings are generally classified into five types based on their materials and how they stand up to fire. Being able to quickly identify which one you're facing gives you an immediate tactical advantage.

- Type I (Fire-Resistive): This is your typical high-rise, hospital, or major public building. They’re built with noncombustible materials like concrete and protected steel, designed to compartmentize a fire. Fires here are often stubborn and hot, but structural collapse is less of an immediate worry.

- Type II (Non-Combustible): Think big-box stores and modern commercial buildings. The structure itself is noncombustible—metal studs, concrete block walls—but the contents are anything but. The big hazard here is early roof failure. Unprotected steel trusses can lose their strength at around 1,100°F and come down on top of you.

- Type III (Ordinary): These are the classic "Main Street, USA" buildings. They have brick or block exterior walls but a wooden interior structure. Fire loves to run through the hidden void spaces in the floors and ceilings, making vertical spread a huge threat.

- Type IV (Heavy Timber): Old mills, factories, and some churches fall into this category. They feature massive wooden beams and columns that actually have a high degree of fire resistance. It takes a lot to get them going, but once they do, you're dealing with an immense fire load that's incredibly difficult to put out.

- Type V (Wood-Frame): This is the most common construction type for modern homes. Just about everything is made of wood, from the structural frame to the floors and roof. These fires can spread like crazy, both horizontally and vertically.

Lightweight Construction: The Hidden Killer

Modern construction is all about speed and cost savings, and that often means using lightweight engineered wood products. Components like I-joists and trusses held together with small metal gusset plates should be a massive red flag during your fire scene size up.

Under fire conditions, lightweight truss systems can fail in as little as 5 to 10 minutes. The gusset plates heat up, pull away from the wood, and the entire assembly can collapse with little to no warning. Identifying these systems is critical for firefighter safety.

Practical Example: You're the first officer arriving at a house fire in a new subdivision built in the last 15 years. You see heavy smoke pushing from the attic vents. Knowing it's almost certainly lightweight truss construction, you immediately consider the risk of roof collapse. That might lead you to order a transitional attack from the outside to cool the attic space before sending your crew onto a potentially unstable roof, preventing a catastrophic failure and saving lives.

Comparing Old vs. New Construction

The age of a building tells you a lot. An older home might be built with balloon-frame construction, where the exterior wall studs run continuously from the foundation all the way to the roof. This creates a clear, unimpeded chimney for fire to race from the basement straight to the attic.

A modern home, on the other hand, likely uses platform framing, which provides natural fire stops at each floor level. But here's the trade-off: it also probably features those dangerous lightweight trusses.

Here’s a quick breakdown:

| Construction Feature | Balloon-Frame (Older) | Platform-Frame (Modern) |

|---|---|---|

| Vertical Fire Spread | Extremely rapid due to open stud bays. | Slower due to fire-blocking between floors. |

| Structural Members | Solid, dimensional lumber that fails predictably. | Lightweight trusses and I-joists that fail rapidly. |

| Primary Concern | Unchecked vertical fire extension. | Sudden, catastrophic structural collapse. |

| Tactical Approach | Open walls and ceilings to check for extension. | Limit time crews spend under or on truss systems. |

By weaving building construction into your fire scene size up, you shift from being a fire fighter to a fire strategist. You start to see the building not just as the box containing the fire, but as a key player in how the entire incident will unfold. This is what allows you to use your resources effectively, get ahead of problems, and ultimately create a safer fireground for everyone.

Matching Your Resources to the Fire

A perfect strategy on paper means nothing if you don't have the crews, equipment, and water to actually make it happen. A huge part of your fire scene size up is taking a quick, honest inventory of what you have versus what the fire is demanding right now. This is where you pivot from observation to logistics, making sure every assignment is backed by the resources needed to get it done.

It’s not just about counting fire trucks; it’s about deploying them smart. The right placement of that first-arriving engine, ladder, and rescue company can buy you precious minutes. You're basically shaping the battlefield in your favor while you wait for the rest of the cavalry to arrive.

Gauging the Need for Additional Alarms

One of the toughest—and most critical—calls an incident commander makes is striking a second alarm. If you wait too long, you’re immediately on the defensive, playing catch-up for the rest of the incident. Here's the thing: calling for help early isn't a sign of weakness. It's the mark of a strong commander who sees the incident's potential and gets ahead of it.

You have to size up the fire you actually have, not the one you hope you have. Practical Example: If your initial engine company is immediately swamped with pulling a line, forcing the door, and starting a primary search, who’s left? Who is handling ventilation, throwing ladders for a rescue, or standing by as the rapid intervention team? Recognizing that personnel deficit in the first two minutes is everything.

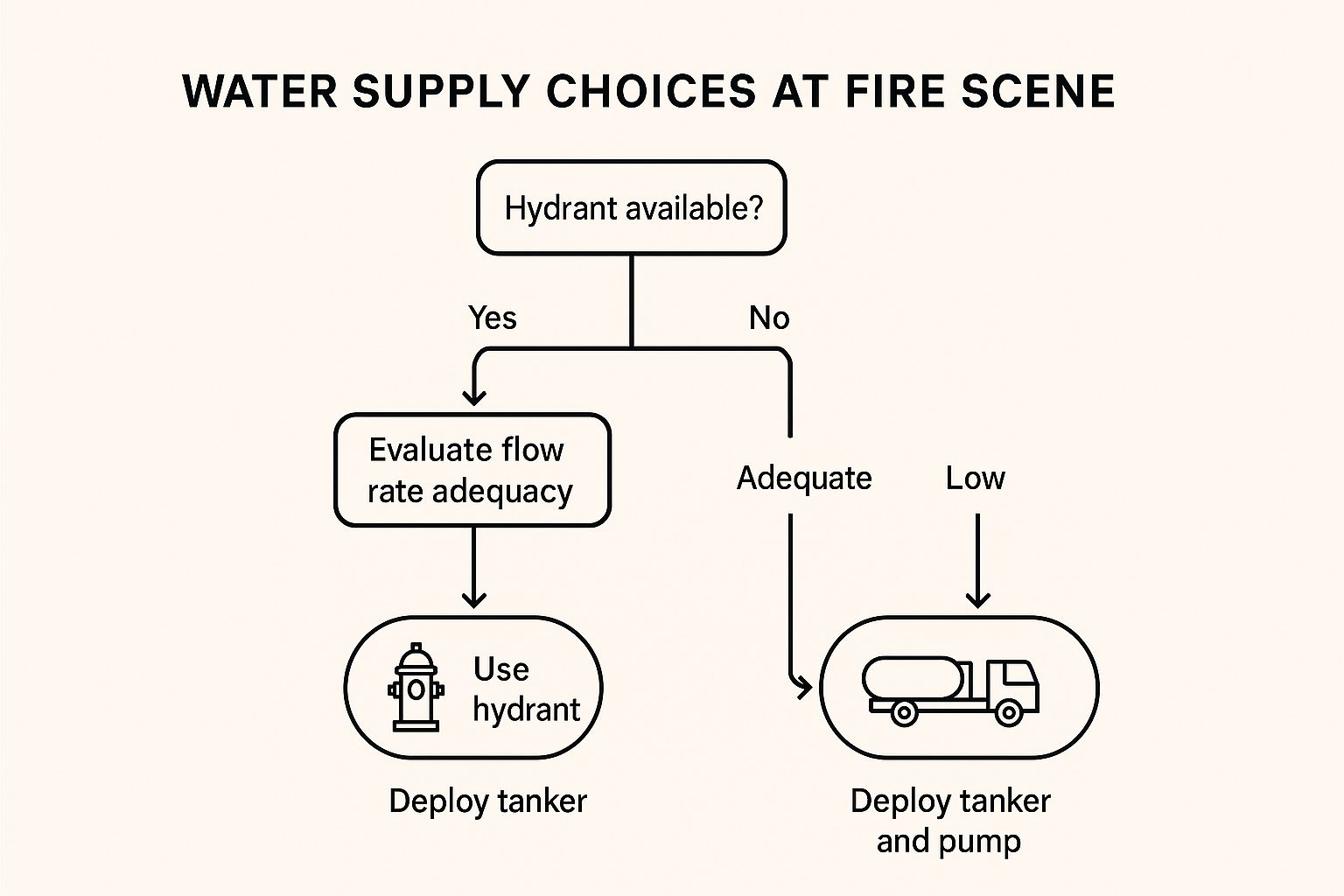

This chart drives home just how critical one resource—your water supply—can be.

As you can see, even with a hydrant right there, a low flow rate changes the game completely. Suddenly, you need to be calling for tankers. It shows how a single variable can instantly alter your entire resource plan.

The consequences of getting this wrong aren't just theoretical. A landmark 1980 Ohio State University study looked at 404 structural fires and found some sobering numbers. When firefighter numbers dropped below 15, the injury rate shot up by 46.7%, and significant fire spread increased by 24.1%. It gets worse. For bigger incidents, when staffing fell below 23, firefighter injuries skyrocketed by 73.5%.

Incident Escalation Guide: When to Call for More Resources

Knowing when to escalate can feel like a gut call, but there are clear indicators that should trigger an immediate request for more help. Waiting until you're overwhelmed is too late. This guide outlines some common on-scene indicators and the appropriate resource requests.

| Incident Indicator | Potential Risk | Recommended Resource Request |

|---|---|---|

| Visible Fire from Multiple Floors/Openings | Rapid fire spread, potential for structural collapse, multiple victims. | Strike additional alarms immediately for more engines and ladders. |

| Reports of Trapped Occupants | Life safety becomes the immediate priority, diverting initial attack crews. | Request specialized rescue/squad companies and additional EMS units. |

| Defensive Operations Declared | Fire is too advanced for interior attack; risk of collapse is high. | Call for ladder pipes, master streams, and a dedicated safety officer. |

| Water Supply Issues (Low Pressure/No Hydrants) | Inability to sustain fire attack, leading to fire progression. | Request a tanker task force and establish a water supply group. |

| Hazardous Materials Involved | Potential for explosion, toxic exposure, and environmental damage. | Call for a HazMat team and establish isolation zones. |

Think of this table as a mental checklist. If you see any of these signs, your hand should already be reaching for the mic.

Specialized Units and Mutual Aid

Not all fires are created equal, and neither are the tools we need to fight them. Your size-up has to quickly spot conditions that demand equipment or expertise beyond what a standard engine or truck company carries.

Just think about these scenarios:

- Vehicle Collision with Entrapment: That immediately screams "heavy rescue." You need a squad with hydraulic extrication tools, and you need them now.

- Confirmed Hazmat Release: This is a whole different ballgame, requiring a specialized hazardous materials team and maybe even a tiered response from regional or state assets.

- High-Rise Fire: This is a resource monster. You'll need multiple ladder companies, specialized high-rise hose packs, and a ton of personnel just for stairwell support and crew rotation.

Beyond the traditional gear, modern departments are leaning more and more on aerial tech. For a really deep dive into how drones are changing the game and giving incident commanders a bird's-eye view, check out Drones Fighting Fires: The Ultimate Guide.

Calling for mutual aid should be a proactive move, not a reactive one. If you're rolling up to a fire in a rural area with no hydrants, or you're facing a large commercial building, requesting tankers or a ladder from the next town over before you're desperate is just smart incident command.

Actionable Insight: Trying to manage this complex web of resources requires a solid system. The features of a comprehensive dispatch platform show how technology can track and deploy critical assets without chaos. This prevents over-dispatching, which saves fuel and reduces wear-and-tear on apparatus, and ensures the right unit gets to the right place faster, directly contributing to smaller fire losses and better outcomes.

At the end of the day, matching your resources to the fire is a constant balancing act. A continuous fire scene size up ensures that as the incident changes, your resource plan changes with it, always keeping firefighter safety and operational effectiveness front and center.

Adapting Your Plan with a Continuous Size-Up

Your first fire scene size-up is a snapshot, a crucial first look. But that's all it is—one moment in a rapidly unfolding event. A fireground is anything but static; conditions can go south in the blink of an eye. This is why the size-up isn't a one-and-done checklist item. It's a constant feedback loop that has to be running in the back of an incident commander's mind from the moment they arrive until the last rig clears the scene.

Thinking of the size-up as an ongoing process is what keeps your strategy from becoming obsolete and, more importantly, keeps your crews safe. A plan based on what you saw ten minutes ago is already dangerously out of date.

Reading the Triggers for a Reassessment

Some events on the fireground aren't just minor shifts—they're blaring alarms that demand you immediately rethink your entire operation. A seasoned IC is always taking in new information, and they know which cues signal a major change in the incident's direction. These triggers are non-negotiable. They're your sign to pause, re-evaluate, and adapt.

Keep your eyes peeled for these critical triggers:

- Sudden Smoke Changes: If that light gray smoke puffing from an eave suddenly turns into thick, turbulent, jet-black smoke, you've got a big problem. The fire has either found a new, richer fuel source or it's become severely ventilation-limited. That's a massive red flag waving, screaming about a potential flashover.

- Interior Crew Reports: A radio call of "high heat and zero viz" from an attack crew is a big deal, especially if they aren't making any headway. It tells you the fire is winning that battle. Another one that'll make the hair on your neck stand up is a report of creaking or groaning sounds—that might be the only warning of structural compromise you're going to get.

- Visible Structural Changes: Any sagging in the roofline, bowing exterior walls, or fresh cracks appearing are signs of impending collapse. You can't negotiate with gravity. Get your people out.

The ability to catch these triggers and act on them without hesitation is what separates a good IC from a great one. It's the discipline of constantly updating your risk-benefit analysis with every new piece of intel, making sure every single decision is grounded in the current reality of the fireground.

A Practical Example of Adapting the Plan

Let's walk through a scenario. You're commanding a fire in a two-story wood-frame house. Your initial size-up shows heavy fire blowing out a single window on the first floor, side Charlie. The strategy is textbook: an offensive interior attack to get a quick knock-down and a primary search. Simple enough.

But ten minutes into the fight, your attack crew radios that they've knocked the main body of fire, but they're now getting cooked on the second floor. At the same time, your outside vent person reports that the lazy gray smoke from the attic vents has turned dark and is now pushing out with some real force.

This is a trigger moment. The fire has extended vertically into the walls and up to the attic. Your initial plan is no longer going to cut it.

A continuous fire scene size-up forces you to adapt, and fast:

- Reassign Resources: You immediately redirect your second-in engine to pull a line to the second floor, getting ahead of the fire and cutting off its vertical path.

- Adjust Ventilation: You order the truck company to get ready for vertical ventilation. You need to get that heat and smoke out of the attic before it compromises the roof structure and drives crews on the second floor to their knees.

- Update Your Risk Analysis: The game has changed, and the risk to your firefighters just went up. You now have crews on two floors, a compromised structure to worry about, and a fire in the attic. You start a mental clock—how long can they operate safely before you need to pull them out?

This is what it's all about. This constant adjustment, driven by what you're seeing and hearing, is how you keep a small fire small and how you manage a dangerous situation without getting anyone hurt.

Techniques for Maintaining Situational Awareness

The biggest enemy of a continuous size-up is tunnel vision. It’s easy for an IC to get so lasered-in on one problem—like getting water on the fire—that they miss the bigger picture and the critical triggers screaming for attention. The trick is to build systems into your command structure that force you to maintain that 30,000-foot view.

- Delegate Monitoring Roles: If you have the staffing, assign a dedicated Safety Officer. Their only job is to do a continuous 360 of the building, watch the fire, and look for problems. Their fresh eyes will catch things you'll miss while you're juggling radio traffic and five other tasks.

- Establish Routine Progress Reports: Make timed progress reports from your division and group supervisors mandatory. A simple report like, "Command from Interior, we're still seeing high heat on Division 2 with no visible fire," is a priceless piece of the puzzle. It forces crews to tell you what's not happening just as much as what is.

Actionable Insight: Switching your mindset from a static, one-time report to a dynamic, ongoing process is the single most important part of a successful fire scene size-up. Platforms like Resgrid automate personnel accountability reports (PAR) and incident timers. This frees up the IC from manual tracking, reducing mental workload and the chance of missing a critical trigger. This enhanced focus directly translates to safer operations and reduces the risk of costly mistakes.

Frequently Asked Questions on Fire Scene Size Up

Even with the best training, some questions just keep coming up on the fireground. You’ll find yourself in confusing situations that test your decision-making. A good fire scene size up isn't a one-and-done checklist; it's a constant process of asking and answering these questions in real time.

This section is all about tackling those common points of confusion head-on. Getting clear on these challenges will help you turn hesitation into confident, decisive action when it counts.

What if Dispatch Information Conflicts With What I See on Scene?

This happens all the time. Practical Example: Dispatch reports a simple trash fire behind a strip mall, but as you round the corner, you see a thick column of black smoke pumping from the roofline of the building itself.

The rule here is simple and absolute: what you see on scene always overrides what you were told.

Your size-up starts the second your own eyes and ears are on the incident. Trust your senses and training. A caller's report is a starting point, not the final word. Your job is to assume the worst until your own size-up proves otherwise. If you pull up and see smoke pushing from the eaves, you immediately upgrade the response based on that visual confirmation, no matter what dispatch said.

How Do I Prioritize Rescue vs. Fire Attack?

This is the classic fireground dilemma. The answer comes from a rapid risk-benefit analysis that's a core part of your fire scene size up.

Your priorities usually follow the RECEO-VS model (Rescue, Exposures, Confinement, Extinguishment, Overhaul – Ventilation, Salvage). But the specific situation dictates the very next move.

- Known Rescue: If you have a credible report of a trapped victim with viable conditions—say, someone visible at a second-story window with smoke behind them—rescue shoots to the top of the list. Practical Example: That first attack line is better used protecting the stairway so the search crew can get to the victim, rather than hitting the seat of the fire in the kitchen.

- No Known Victims: If there isn't an immediate, known life hazard, the fastest way to make the entire building safer is to get water on the fire. In these cases, an aggressive fire attack is the rescue.

A fast, aggressive, and well-placed initial attack line solves most problems on the fireground. By confining and extinguishing the fire, you are actively protecting any potential victims you haven't found yet.

When Should I Call a Second Alarm?

Hesitation is the enemy here. It is always, always better to have more resources coming that you can cancel than to need them and not have them. You need to call for help early, based on the potential of the incident, not just what's burning the moment you arrive.

Look for these triggers to make the call:

- A working fire in a large or complex building like a strip mall, school, or hospital.

- Any credible report of trapped occupants that's going to tie up your initial crews.

- Serious water supply issues or any significant delay in getting that first line in service.

Actionable Insight: Getting ahead of the resource curve is the mark of a strong incident commander. Managing a complex scene takes clear communication and organization. The Resgrid support and documentation section provides information on how a system can streamline mutual aid requests and track incoming units. This automation reduces delays and confusion, which can save critical minutes when a fire is doubling in size, potentially saving thousands in property damage.

A methodical fire scene size up is the cornerstone of every safe and effective operation. To ensure your team is always connected and your resources are managed efficiently from dispatch to the final report, Resgrid provides a unified platform to handle it all. See how our system can support your command structure by visiting https://resgrid.com today.